In English, we read the book 1984 to study one of the most celebrated narratives of our time and wrote our own short story. In English Honors, we read a book of short stories of our choosing—I chose Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies—and wrote an imitation short story of our own.

To prepare for short story writing, we went back to the basic building blocks of stories. We worked on developing characters through exercises like the “character questionnaire” where we answered a list of questions like we were a character that we had designed. We also looked at how to construct a plot by studying different formats for basic story structures and through exercises like creating a plot map.

My short story is about a 28-year-old man who is reluctant to move forward in life and is stuck trying to squeeze joy out of his memories, more specifically his 8th birthday. In the story, he puts on an “imitation birthday” to try and relive his experience. I thought of this idea because I wanted to produce a snapshot of somebody’s life, a realistic story that could provide the reader with a chance at introspection. I wanted to look at themes of “moving on” through hardship and emerging a new person.

My imitation short story is about an old married couple in the autumns of their lives. Their marriage is dying, and while the husband seems content, the wife wants something more. She finds it in an affair with one of their neighbors. The tension builds as she fears her husband might found out about her secret… it was an imitation of Lahiri’s writing, so I was inspired by several common themes in her work, namely failing marriages and the immigrant experience. Her writing is also often a snapshot of realistic characters’ lives, with no fantasy-like resolution, so I tried to model my imitation after this aspect as well.

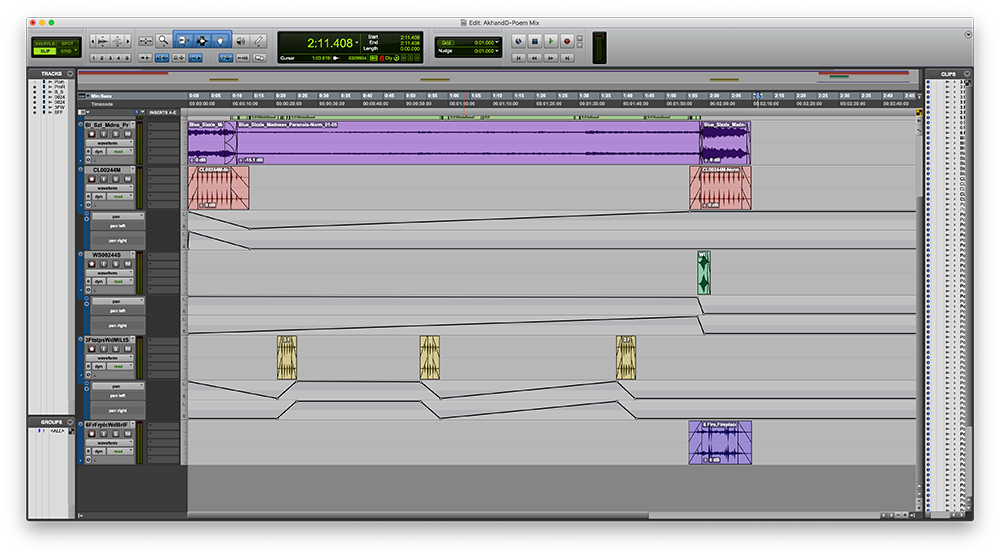

In Digital Media, we recorded our short stories and edited them together with music and sound effects. I used my Tascam Audio Recorder to capture the audio before importing it into Pro Tools to edit and master it. Pro Tools isn’t an Adobe Program, so while there is some overlap in the Adobe suite, ProTools requires more time and effort to master if you are new to it. Luckily, we have gotten a great deal of practice in ProTools, so I was able to use it more easily this time.

Short Story: “Yesterday”

He let the cool air wash over him and closed his eyes. He licked his lips. Chocolate. No, strawberry. No, both. And vanilla. He opened his eyes, bent down, and plucked a Neapolitan ice cream cake from the bottom rack of the freezer, placing it carefully in the shopping cart.

He looked down at the cart. The cake, red and white balloons, and a sparkle-covered number 8 candle. Party hats and a HAPPY BIRTHDAY banner, both decorated with cartoon animals. Generic-branded cola and barbecue and sour-cream-onion chips. Styrofoam plates. Crepe-paper streamers. He continued to the check-out line.

“Kid’s birthday?” asked the cashier. “Looks like you invited the whole class!” She went on to describe her child’s most recent party.

“He had to have this specific cake, the brand-name chips, everything had to be blue. You know, he told me what napkin size to get—napkin size, can you believe that? It was his fifth birthday and he threw a fit about how we didn’t have any large napkins. Unbelievable.”

He smiled, keeping his eyes low. He said nothing. The cashier stared at him, expecting a comment, or at the very least, a laugh.

“Honey, you there?” she asked.

He tried to stutter a response, but nothing came out other than a squeak. He still didn’t look the cashier in the eye.

The cashier waited another moment before sighing and saying, “Alright, thirty-four-sixty-four.”

He paid and left.

***

Back at his apartment, He put the cake in the freezer and the other party paraphernalia on the kitchenette counter. He walked to his living room and closed his eyes. He frowned, concentrating. Table at the center of the room. Banner on edge of table. Streamers—where were the streamers?

He moved the coffee table, carpet, and sofa to the side and dragged his dining table to the center of the room. He grabbed a single chair and placed it at the head of the table. He poured the chips into two bright-yellow plastic bowls. He went to the pantry, retrieved a bag of popcorn, and poured it into a third bowl. He placed the three bowls next to the four bottles of cola, a stack of red solo cups, and the styrofoam plates.

He hung up the banner on the edge of the table with painter’s tape. He used the same to hang up the streamers: a half-dozen above the door, and the rest on the ceiling, colors distributed evenly. Red, then green, then yellow, then blue, then orange, then purple, in neat rows.

He took the cake out of the freezer and placed it on the table in front of the chair. He placed the “eight” candles on the cake. Perfectly centered. He walked to a corner of the room so that he could see it in its entirety. He closed his eyes for a minute, and when he opened them he dissected everything in the room. He spent two minutes just standing still and looking. Comparing. He frowned. It wasn’t right.

He went to the door and took the streamers down, redistributing them among the others on the ceiling, taking care to keep the color pattern consistent. He put the chair and the cake on the other end of the table.

He walked to the same corner and repeated his exercise. He frowned again. He was growing more frustrated. This time, it was the snacks, the banner, and the absence of music that were the issue. The popcorn wasn’t right; he threw it out and replaced it with pretzel sticks. He started to take the HAPPY BIRTHDAY banner down—it was supposed to be above the door—when the doorbell rang. He put down the sign and walked to the door. He opened it more forcefully than he had meant to. He was greeted by a startled woman in an orange Little Caesars uniform holding three boxes. He realized he was glaring, and blushed, embarrassed. His heart quickened its pace, and he looked down.

“Forty-five-oh-nine,” she said. He murmured “sorry” and gave her $50. He took the pizza—two cheese, one pepperoni, both large—and closed the door. He set the pizza at the end of the table opposite from the cake.

He went back to moving the banner. He grabbed a stool from the kitchen and hung it above the door, taking care to make sure that it was lopsided: slightly lower on the right than it was on the left.

He went to his bedroom and grabbed the clean Limp Bizkit CD he had begged his mother for. She wouldn’t let him get the one with the “swears” in it. He went back to the living room and inserted the CD into his audio system.

He stepped back to his corner and repeated his exercise. He closed his eyes tightly, this time for five minutes. He imagined the banner, the snacks, the cake. The streamers, the generic-branded cola, the hats. The music playing in the background. He smiled. It was ready.

***

He walked around the room, admiring the decorations, from the multicolored streamer to the perfectly lopsided banner. He took a plate and ate two slices of pizza—only cheese, not pepperoni. He hated pepperoni. He ate some chips and drank a cup of the generic-brand cola that his mother had told him was more “economical”. He hummed along to the music playing. After he finished eating, he washed his hands and grabbed a knife, preparing to cut the cake. He paused the music and made his way over to the table. He was blushing, excited.

He sat down in the chair at the head of the table, in front of the ice cream cake. He withdrew a Bic lighter from his pocket, lit the eight candle, and closed his eyes. He shut them tight, tight, tight, until they ached.

He heard children laughing and chatting. He opened his eyes and saw his friends standing around him. They were pushing and jostling to get closer to the birthday boy. His mother leaned down over his shoulder, struck a match, and lit the “eight” candle. And then the singing began: twenty children and his mother, all off-key and out of tune. But it was the most beautiful thing he had ever heard. He looked around the room and looked at everything: the empty pizza boxes, the cola, and the chips; the banner, the streamers, the balloons; and the twenty smiling faces wearing animal party hats.

The song ended and the group cheered. He closed his eyes, soaking up the sights, the sounds, and the feelings. He opened them, and he realized he was crying. The laughter, the cheers, the friends, and his mother were gone. It was just him, all alone, without anybody there to sing, to cheer, to listen. The “eight” candle was dripping wax onto the cake.

He spent the few hours cleaning up the party decorations. Down came the banner, the streamers, the balloons. In the garbage went the pizza, the cake, and the party hats. He threw away the remaining chips, the soda, and the styrofoam plates.

He found himself staring at the jumble in the garbage can. All the memories of his birthday, the only evidence it had happened. Soon to be tossed carelessly in the trash, to be taken, crushed, and incinerated. All those supplies had so much use left in them, so much potential. How needless it had been; all that effort wasted on just one person.

He stared at the mess, slowly collapsing onto itself, and stood there staring at it. He resolved to get rid of it tomorrow, or the day after. He would take care of it later.

He began trudging away from it, back to his bedroom, when he stopped. If he ignored it, it would start to smell. He had to do something about it soon.

He woke up the next morning to a clean house. He had cleansed the remnants of the previous day. Everything was behind him.

It was a new day.

Imitation Short Story: “The Chatterjees’ Autumn”

It had been months since the last time Mr. and Mrs. Chatterjee had discussed anything unrelated to the keeping of the house, the barbershop, the television programming for the week, and whether they wanted Chinese or pizza for dinner–only takeout, of course, as they were getting too old to go “out on the town,” as Mrs. Chatterjee liked to say. Not that they could, of course; the entire town shut down at 6 p.m., save for a 24-hour Denny’s.

They were both reaching 60 after 40 years of marriage. Their 41st was coming up in a few weeks, but there wouldn’t be much ceremony. They had agreed a few years back that there would only be gifts for Christmas and birthdays, which they bought for themselves.

Truth was, there wasn’t much ceremony in anything they did anymore. Mr. Chatterjee went to the barbershop at 10, cut hair till 5 (with a break for lunch), then went home. Mrs. Chatterjee milled about the house, occasionally tending to her vegetable patch, which she placed in the front yard so that she could chat with passers-by. She timed her dinner preparations so that she finished at 5:15, right when Mr. Chatterjee came home.

Today, she had spent her afternoon harvesting this season’s crop of baby tomatoes. There were two.

Mr. and Mrs. Chatterjee sat down to their lamb and two baby tomatoes. As Mrs. Chatterjee was serving the curry in the silver dish some uncle or the other had gotten them for their wedding, Mr. Chatterjee turned to her and said, “What am I living for anymore?”

Mrs. Chatterjee paused. She set down the silver dish and looked at him, truly looked at him for the first time in she couldn’t remember how long. His creased face, his strangely straight teeth, the few hairs he had left on his head that he stubbornly demanded he comb. His wet lips that he kept licking, which he parted to ask again, “Reema, what do you think I’m living for?”

She was about to respond with a what do you mean? before he cut her off. She knew that he saw her lips part, and yet he cut her off.

“When I was a child I lived for myself. When I was in my twenties I lived for you. In my thirties and forties, I lived for our children. Now, what am I living for?”

He delivered this monologue with ease. He had rehearsed. The question was concise, open, and ambiguous–loaded. Mrs. Chatterjee wondered what had prompted her husband to ask it. Maybe it was how, over the course of the past few months, her lips had become fuller, her perfume stronger, her nail polish brighter.

Dread set in. He must have recognized that she was changing. Did he know why? She knew why, why she felt lighter, sunnier, freer.

Mrs. Chatterjee began seeing Harry four months ago, in the middle of the rainless summer. He was five years younger than she was—not that it made a difference at their age, he would say. She was watering her vegetable patch when he walked up to the fence. She didn’t remember what he had come to ask her, but she did remember that she offered him a glass of lemonade. It was something she saw a character do on Friends, the TV show she watched to learn about American culture when they had just moved here.

As Harry had sipped his lemonade, sat where Mr. Chatterjee was sitting right now, Mrs. Chatterjee remembered staring at his eyes, gray, smiling, and surrounded by the deepest crow’s feet she had ever seen. She finally understood what people meant when they said that the eyes were the “window to the soul”. He caught her looking, and she blushed, but her gaze didn’t waver. He smiled, and so did his eyes.

“What am I living for?” rang her husband’s question, again. Mrs. Chatterjee snapped out of her daydream. She sat in silence. She looked at him and cocked her head. He sighed, as if he knew she had no reply.

“Nevermind,” he said. “Pass the lamb. Please.”

***

From an outsider’s viewpoint, the next week was the same as the last had been. There were no changes in Mr. and Mrs. Chatterjee’s daily lives. The two went about their respective businesses, Mr. Chatterjee’s being the barbershop and Mrs. Chatterjee’s being the garden.

Today, the business was particularly slow. Mr. Chatterjee had swept the floor three times already and had resolved himself to looking through a stack of old Better Homes and Gardens magazines that he used to decorate the table in the waiting area. His mind was swimming with thoughts about The Dinner, as he had started referring to it in his head with some amusement.

It had been seven days since Mr. Chatterjee had delivered his dinner-table speech, but the look Mrs. Chatterjee gave him hadn’t escaped his memory: panic, masked by contrived confusion. She must have known what he was trying to get at; that’s why things were so tense. He had tried to broach the subject previously, but he had just been met with you’re being ridiculous! or of course not!.

He didn’t understand why Mrs. Chatterjee was so nervous about discussing getting a dog. They had owned dogs in the past when their children were still young. And it wasn’t like they couldn’t care for one; Mrs. Chatterjee was home all day, and they didn’t take vacations anymore. They could get an adult dog so that they wouldn’t have to put in the work of training a puppy. A slow, wise animal, like a St. Bernard or a Mastiff.

The bell above the barbershop’s door jingled and Harry walked in. Mr. Chatterjee smiled, welcoming him, and ushered him into the chair.

“What will it be today, Harry?” Mr. Chatterjee said in his Indian-tinged American accent, reserved for outside-the-house use, as he threw the cloak over him.

“The same that it is every week, Ramesh,” said Harry with a chuckle.

Mr. Chatterjee cut hair in silence. Other barbers liked to chat with their clients, but he thought that doing so made them unprofessional. Besides, most customers appreciated the lack of awkward conversation; they could just close their eyes and listen to the Muzak playing in the background.

Mr. Chatterjee finished Harry’s haircut, collected the $20, and swept the store a fourth time.

***

At 5:15, Mrs. Chatterjee heard their car pulling into the driveway. She was spooning rice into a serving bowl as Mr. Chatterjee walked in. She placed it on the table next to the bowl of chicken curry and plate of cucumbers and carrots.

After the ritual minute of hello-hi-how-was-your-day-it-was-fine, they settled down to eat in silence. Mr. Chatterjee wanted to say something to follow up last week’s monologue. The speech he gave a week ago was perfect–a carefully crafted layer of groundwork that would allow him to build his argument for getting a dog over time.

He thought for another few minutes, watching Mrs. Chatterjee spoon chicken and rice into her mouth. Mrs. Chatterjee paused and looked up at him.

“Why aren’t you eating?” she asked.

Mr. Chatterjee snapped to attention.

“Reema, I’ve been thinking about what I said last week,” he said.

Mrs. Chatterjee froze mid-chew. She set her spoon down, swallowed, and looked at him.

“What about it?” she asked in a quiet voice.

“I want to talk about a change,” said Mr. Chatterjee in a somber tone, “that I think will be good for the both of us. Ever since the kids left the house, I know that things have changed between us. For the worse. And I want to revitalize our marriage, and I think I know how. But–”

Mr. Chatterjee was interrupted by a violent cough, and then another, from Mrs. Chatterjee. They turned into a coughing fit that sent tears streaming down her face. She got up and ran to the bathroom. Mr. Chatterjee sat in his seat, frozen from shock and confusion. He heard retching, then the sound of the toilet flushing. Mrs. Chatterjee exited the bathroom, saying that she felt ill and that she was going to bed.

Mr. Chatterjee began to slowly get up to help her, but she said that she was fine and not to worry. He sat down to finish his dinner but only ate a few more slices of cucumber and carrot before he threw the rest away. That night, he slept on the sofa.

***

“It was terrible, Harry,” said Mrs. Chatterjee. “I ran to the bathroom, forced myself to vomit, and told him that I was ill. He slept on the sofa. When he came in to get ready this morning, I pretended that I was asleep. I was too nervous to talk to him.”

She turned to look at Harry. They were lying in her bed. It was 1:00 p.m; Mr. Chatterjee wouldn’t be home for at least another four hours.

“He knows. I just know he knows,” said Mrs. Chatterjee. “I don’t know how, but he must. He’s been trying to bring it up during dinner for the past week, saying things like, ‘my life has no meaning,’ and, ‘things are different between us’. He’s trying to get a confession out of me. And it’s getting to me. I’m starting to crack, Harry.”

“How could he possibly know, Reema?” Harry said. “We’ve been so careful. Carefully scheduling, covering our tracks–and besides, you won’t have to hide it for much longer. We’re going to leave soon.” He sat up and cocked his head to the side. “Aren’t we?”

“Harry…” began Mrs. Chatterjee, trailing off. “I don’t know. I need some more time. To get things in order, to tie up loose ends. And I have to think about my children, and how I’m going to tell them.”

Harry was silent. He got up and began putting on his clothes.

“Harry, don’t go,” said Mrs. Chatterjee. “We have a few more hours, at least.”

Harry ignored her. He finished getting dressed and began walking out of the bedroom.

“Just make up your mind, Reema,” he said, as he vanished from her sight and out the back door.

***

Mr. Chatterjee had spent the next day preparing for the final push. He had run through exactly what he would say in his head and was adding the finishing touches as he drove home.

He pulled into the driveway and walked up to the front door. His hand rested on the door’s handle for an extra moment before he opened it. He found Mrs. Chatterjee sitting at the table with a solemn look on her face–she had been waiting for him.

Mr. Chatterjee slowly walked over and sat down. He stared at Mrs. Chatterjee, waiting for her to say something. His father had told him that the best way to win an argument was with silence–make the other person uncomfortable. So he sat, unspeaking; but he was growing more nervous every moment, her bulging brown eyes cutting into his.

He was the one to break the silence.

“Reema, things have changed between us. And we need to address it.”

Mrs. Chatterjee said nothing. She opened her mouth as if to say something, but closed it and looked away. She shifted in her seat.

“I think you know why I want to have this conversation. I’ve tried to address it in the past, but you’ve ignored me. I don’t want to let this go any longer. Reema, I want a d–”

“Ramesh, I’ll stop the affair!” exclaimed Mrs. Chatterjee with anguished eyes.

Mr. Chatterjee’s mouth hung open for a beat before he finished his sentence: “–og. I want a dog. Affair? What do you mean affair?”

He sat up straighter, leaned in, resting his elbows on the table.

Mrs. Chatterjee was frozen, except for her twitching eye. They sat staring at each other for another few seconds before Mrs. Chatterjee began to sob.

She got up and rushed to the bedroom. Mr. Chatterjee followed her and stood silently in the doorway, watching her. She retrieved a dusty suitcase from on top of their armoire and, without bothering to clean it, haphazardly stuffed any of her belongings that she could find in it. Clothing, jewelry, pictures–all of it was jammed into any crack of space she could find among the other items.

Mr. Chatterjee just stood there, watching her. He had absolutely no clue as to what he could have done, what he should have done. Mrs. Chatterjee, still sobbing, had finally finished her packing. She hadn’t looked at him once. She picked up the phone and dialed a number.

“Harry? Harry? Come. Now,” she said, through her tears.

Mr. Chatterjee was crying now as well as he pieced together what she was saying. He walked to the living room and sat on the sofa while she remained weeping in the bedroom. Five minutes later, the doorbell rang. Mr. Chatterjee didn’t move.

Mrs. Chatterjee came out of the room with her suitcase. She opened the door and thrust her suitcase onto the waiting Harry. She ran to his car and he began to follow, but not before he saw Mr. Chatterjee. They made eye contact for a split second before Harry looked away and scurried after Mrs. Chatterjee, closing the door behind him.

Mr. Chatterjee remained seated. He breathed a sigh of relief; it was as if he had been waiting for something like this to happen. The tension had been cut, the rubber band snapped. And it wasn’t his fault. For the first night in a while, Mr. Chatterjee slept easily.

***

It had been over a week since Mrs. Chatterjee had left. It was Sunday, the only day on which Mr. Chatterjee closed the shop early, at 4:00. Mr. Chatterjee was sitting on his front porch with his eyes closed, basking in the golden glow of the dusk when Harry’s car pulled up. He was petting a massive, old St. Bernard that was sitting silently next to him.

Mrs. Chatterjee stepped out of the car with a folder in hand. Harry kept staring straight ahead, not even glancing at Mr. Chatterjee. Without a word, she walked up the porch stairs and handed it to Mr. Chatterjee with a pen. They were divorce papers.

Mr. Chatterjee flipped through them and signed them, nonchalantly. He handed them back to her. Mrs. Chatterjee stood in front of for a moment, expecting a response of some sort. He stared at her. When it became apparent that he wasn’t going to give her one, she let out a sigh and trudged back to Harry’s car, divorce papers in hand.

Mr. Chatterjee watched them drive off and went back to his half-sleep, petting his dog. He heard nothing but panting and the birds. He was at peace.