Narrative Visual Perspective in English

Introduction

In the second semester of English, we began with the Lyrical Essay unit, which introduced us to lyrical essays and what differentiates them from other forms of written work. Often autobiographical in the examples we read (The Book of Delights by Ross Gay), lyrical essays can combine nonfiction writing with personal voice, poetry, and figurative language. The main project for this unit was taking what we had learned and creating a lyrical essay of our own.

I chose to write about something very important to me: video games! So maybe playing games is just a silly interest, but a lot of them have actually become the defining parts of different eras in my life. I have a lot of nostalgia for games I used to love, and I’m always searching for more to experience. For my essay, I was specifically interested in the ways the medium can be used to convey important narratives about topics like mental health.

Conquering the Mountain: A Lesson in Video Games

by Allison Teo

The cartridge locks into place with a series of familiar noises, a familiarity that takes you back years and wraps you in a decidedly comfortable hug. Click. Click. You load up the video game, and a short, cheery tune plays. You hum along by instinct. Pixels appear on cue, dancing before your eyes in a pre-programmed sequence meant to make you feel a sort of childlike excitement. It works, of course, just like it does every time.

You’ve always believed there was something special about games and the worlds and characters they introduced you to. You grew up with them, so naturally it would be this way. But still, after all those years of living and learning and aging, it seems as though things should have changed. Yet they haven’t. Time and time again, you are still inexplicably drawn back to that thrilling experience, so much that you can’t stop coming back for more games, more stories, more adventures.

When it comes to psychological studies, video games have somewhat of a bad rep. Influences on violent behavior and addiction come to mind immediately, to a point where the general public’s perception of games are saturated with similarly negative statistics. Although certain statements on harmful impacts hold truth, video games are just as much an open-ended medium for storytelling as films and television. They have equal potential to be uplifting to players as they do to be detrimental, and generalizing all video game experiences as the latter ignores the overwhelmingly positive impact that they have on many people’s lives.

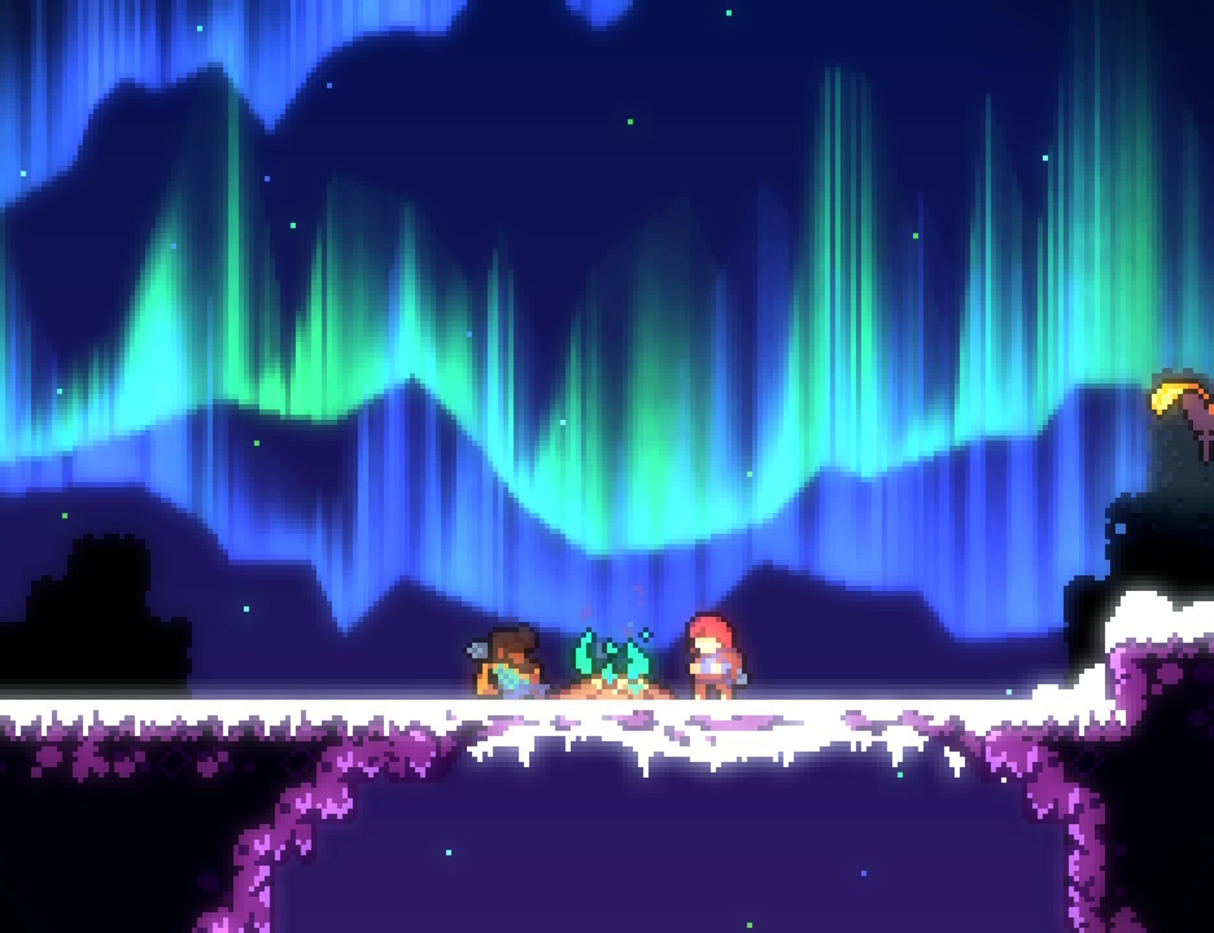

Last year, I played the 2D platformer game called Celeste, and this pretty pixelated game certainly made an impression on me. A big enough impression, in fact, that I went ahead and wrote this essay to talk about it. While plenty of media draws fans through inventive worldbuilding, Celeste is incredibly grounded in its storytelling. In this game, you play as Madeline, an amateur mountain climber whose goal is to scale the titular mountain. Of course, the classic mountain allegory– we all know it– in which our protagonist overcomes adversity and bests the greatest challenges the world has to offer.

What I admire about the writing of Celeste is that it’s simply and completely transparent about Madeline’s challenges, or her figurative mountain. She struggles with depression and anxiety, which is something that you, as the player, learn directly from her dialogue. As the story progresses, you experience what Madeline is feeling through both in-game writing and the nature of the gameplay itself. She discovers that Celeste Mountain is no ordinary climb; making her way up to the peak entails coming face to face with physical manifestations of her internal fears and intrusive thoughts.

At the climax of the storyline (but not that of the mountain quite yet), Madeline confronts the shadowy clone of herself known in the game as “Part of You.” She’s been following our protagonist closely throughout each chapter of the game, even going so far as to harm Maddy to prevent her from reaching her goal. This particular moment is one where she decides that she’s ready to depart from this Part of Her, representative of the turning point in a typical success story: instantaneously “getting better” from mental illness and finding smooth sailing from there on out. However, things aren’t that easy in real life, and Celeste captures this truth by building up hope as Madeline nears the end of a difficult journey and then tearing it away from her hands just as easily. She plummets down, down, down to the lowest point the player has seen yet. From this vantage point, climbing back up the mountain seems far more unattainable than ever before.

This scene is as effective as it is heartbreaking, because it portrays an experience with recovery that is realistic to many lives. The path of recovery is not linear by any means. And in Celeste? It’s not until Madeline accepts both parts of herself that she finds the words to explain why she needs to overcome the mountain so badly in the first place. For the first time, she sits down and talks to Part of Her with the intent to listen, and they both come to terms with the challenges she faces. She realizes that there was no way she would be able to make it if she was quite literally fighting herself the entire way. This is the true turning point of the story, subverting the expectations of the player and empowering Madeline to finally reach the top of Celeste Mountain with the help of a new friend.

I’ve truly never played a game that deliberately encourages your efforts and growth alongside those of the main character as much as Celeste does. Fellow traveler characters like Theo give Maddy comfort and encouragement, even passing on knowledge about coping skills for anxiety. Despite my rapidly growing death count, there wasn’t a moment in which I felt demotivated to push through the more challenging segments of platforming. The difficult gameplay perfectly aligns with Maddy’s motivations and troubles, utilizing the interactivity of video games to capture empathy from the player in a way unique to the medium. That’s the value of playing games, I think.

Storytelling is essential to our way of life, as much as basic necessities are, because stories are the foundations of knowledge and culture. Everybody has their preferences in terms of how they enjoy consuming them, whether it’s from literature, movies and TV, podcasts, or anything else. Titles like Celeste prove to me over and over again that I will always be an advocate for video games as a lasting and meaningful form of storytelling. Also, games are just really fun.